I was standing on an escalator in London, riding down into the Underground with a copy of Rolling Stone magazine. It was late 1971 and I was not happy. Life had rolled easily for me at school: out in the world I was foundering. A junkie girl – another lost middle-class kid like myself, only further adrift – tried to talk to me, her fingers yellow with tobacco smoke as they clawed at the handrail. I glared at her in self-protection. “My god”, she said: “Why are you staring daggers at me like that?” She moseyed away and I stalked off down towards the deep gun-barrel horror of the Northern Line.

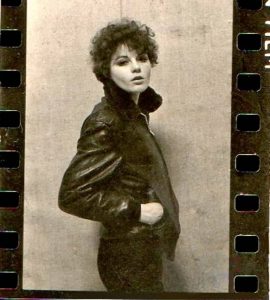

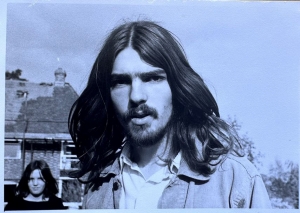

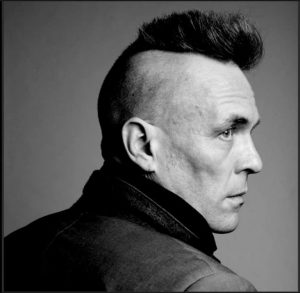

Robyn Hitchcock and sister Lal, Summer 1972

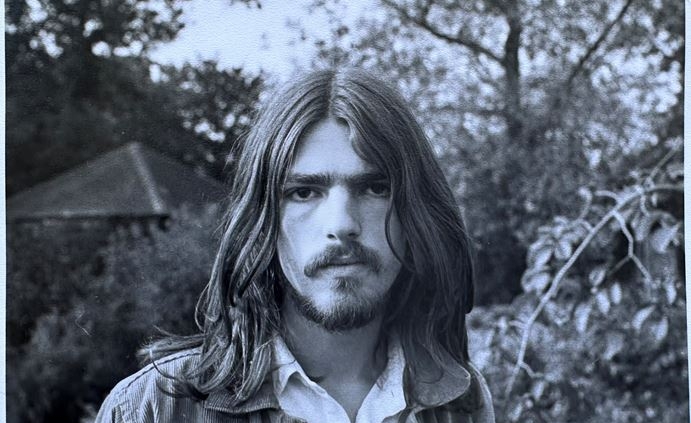

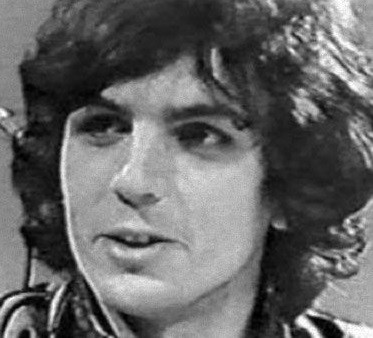

But my mind was elsewhere already. On an inside page of Rolling Stone I had seen a headline: ‘The Madcap Who Named Pink Floyd’ and beneath it a striking photo of the saturnine, spooked Syd Barrett. “According to who you speak to, Syd Barrett is either dead, in jail or a vegetable. In fact he’s alive, and as confusing as ever…” the article began. I read on, transfixed. I knew who Barrett was, of course, or had been – his music with Pink Floyd was my favourite part of them: but I’d never thought to follow him beyond that. Word from my groovier friends was that Syd’s solo records were ‘disappointing’.

I stood by the entrance to the platform and sank my attention further into the article. It depicted a bright, successful young man who had run out of momentum and was back in his mother’s house in suburban Cambridge, emerging from the cellar where he now lived for the interview (which turned out to be the last he ever gave). I didn’t know yet any of the details of his breakdown, his ejection from Pink Floyd, or his slide into inertia. His turn of phrase was striking: “I’m treading the backward path…full of dust and guitars”…”I walk a lot – 8 miles a day: it’s bound to show but I don’t know how.” Barrett spoke in illuminating fragments. “Look at those roses…of course, once you’re into something…” The writer talked about Syd’s ghostly, poetic beauty; and then described how, in a burst of enthusiasm, the ghostly poet showed him a neatly typed manuscript of his lyrics. Syd’s favourite, apparently, was ‘Wolfpack’ from his second (and last) solo album. My train pulled into the tube station and pulled out again. The junkie girl moved up and down the platform, working the passengers. I read on, magnetised:

“Beyond the bar winds

Of the reflecting electricity eyes, tears

Life that was ours grows sharper and stronger away and beyond;

Short wheeling, fresh spring

Gripped with blanched bones

Moaned, magnesium proverbs and sobs.

Howling the pack in formation appear

Diamonds and Clubs, light misted fog of the dead

Waving us back in formation the pack

In formation.”

I was hooked. This was it. To me, Syd Barrett made a trifecta with Bob Dylan and Captain Beefheart. This was what rock lyrics were all about: could be all about, taken to the furthest extreme. The way Barrett conflated wolves with playing cards was neat enough; but the surge, the mania, the sheer demolition in the whole song was beyond magic: it echoed how I was feeling as I headed for 19 years of age.

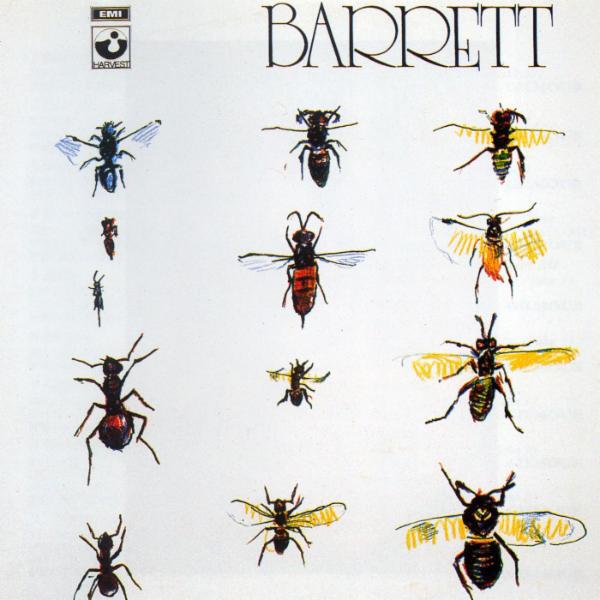

Before long I’d bought the “Barrett” album with Syd’s drawing of insects on the cover, and I’d disappeared into it. Whether I ever came out of it fully again is questionable. Just as I had absorbed Dylan’s ‘Visions of Johanna’ on entering my teens, I exited them by virtually becoming ‘Wolfpack’. There should be more songs like this, I thought, and I tried my utmost to write them.

But I can only express me – though I can *inhabit* Syd’s songs easily enough – and I have, thankfully, never lived through a psychotic breakdown. At a guess, this song seems like one of the last that he managed to write, or at least to finish. As with ‘Visions Of Johanna’, the surreal intensity of ‘Wolfpack’ chimed with what was already inside me; it also set the bar high, gave me something to aim for – and miss, of course.

There’s a truth in there that is conjured by words but lies beyond them.

“All-enmeshing, hovering” – indeed. Thank you Mr B, wherever you went…

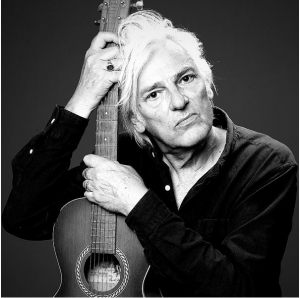

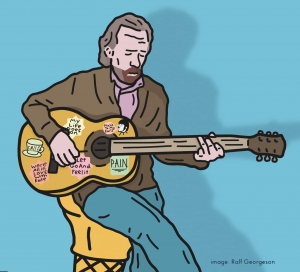

With a career now spanning six decades, Robyn Hitchcock remains a truly one-of-a-kind artist –surrealist rock ’n’ roller, iconic troubadour, guitarist, poet, painter, performer.

Robyn Hitchcock 2024

Lee

Lee

Mick Rock

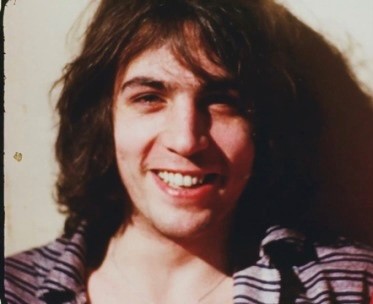

Mick Rock

“

“

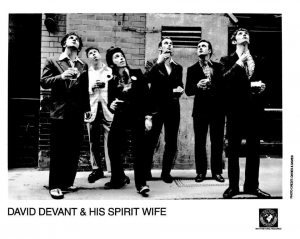

Musician and artist Mikey Georgeson is perhaps best known for his time in the late ’90s and early ’00s as the frontman of art rock band David Devant & His Spirit Wife. Georgeson performs as The Vessel, through which English stage magician David Devant would supposedly express himself. The Vessel told Brighton’s Punter magazine: “It’s quite simple really, as a magician Devant didn’t really fulfil himself so he said ‘I shall walk down the corridors of contemporary music’, so he chose us. I am his vessel.” As The Vessel, Mikey was once sawn in half by spectral roadies and on another occasion fired from a cannon, appearing at the opposite end of the Duke of York’s cinema, clothes tattered, and face blackened from the explosion. Mikey is a Doctor in Fine art and has recently developed a line in performative keynote speeches as a mythopoeic figure Professor Kimey Peckpo. The latest David Devant and his Spirit Wife Lp is at

Musician and artist Mikey Georgeson is perhaps best known for his time in the late ’90s and early ’00s as the frontman of art rock band David Devant & His Spirit Wife. Georgeson performs as The Vessel, through which English stage magician David Devant would supposedly express himself. The Vessel told Brighton’s Punter magazine: “It’s quite simple really, as a magician Devant didn’t really fulfil himself so he said ‘I shall walk down the corridors of contemporary music’, so he chose us. I am his vessel.” As The Vessel, Mikey was once sawn in half by spectral roadies and on another occasion fired from a cannon, appearing at the opposite end of the Duke of York’s cinema, clothes tattered, and face blackened from the explosion. Mikey is a Doctor in Fine art and has recently developed a line in performative keynote speeches as a mythopoeic figure Professor Kimey Peckpo. The latest David Devant and his Spirit Wife Lp is at

It was then that I learned what a challenge it had been for Syd in his mid-teens to adjust to losing his own father. I later dared to speculate upon his loss in my novel

It was then that I learned what a challenge it had been for Syd in his mid-teens to adjust to losing his own father. I later dared to speculate upon his loss in my novel

From the release of See Emily Play and the finishing touches to the debut album, including the segment known as Sunshine, in June of 1967, there is a world of difference to what followed on the shadow side in August and later that year. Merely a few days after the “Piper” release, in early August, Pink Floyd rush-recorded Syd’s Scream Thy Last Scream – with Syd in a bad state and not doing the vocals. This change is what lay on the other side of Bike. That room of noise entered in Bike, a foreboding of what can be found on “the dark side”.

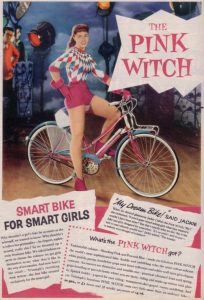

From the release of See Emily Play and the finishing touches to the debut album, including the segment known as Sunshine, in June of 1967, there is a world of difference to what followed on the shadow side in August and later that year. Merely a few days after the “Piper” release, in early August, Pink Floyd rush-recorded Syd’s Scream Thy Last Scream – with Syd in a bad state and not doing the vocals. This change is what lay on the other side of Bike. That room of noise entered in Bike, a foreboding of what can be found on “the dark side”. We only know of one live performance of the song. It was included in the pivotal concert Games For May on May 12, 1967. Possibly this was the only time. Disc & Music Echo heralded Pink Floyd as “the first pop group to appear at London’s swank new Queen Elizabeth Hall, which opened a couple of months ago beside the Festival Hall on the Thames South Bank”. Peter Jenner explained at the time that they “hoped to present a show of completely new material with tapes and films”. For Bike, Julian Palacios writes that a bicycle was “mounted with contact microphones to pick up the sounds of its rotating gears and ringing bell. Two mechanical toy ducks, mounted atop Plexiglas cabinets stage-front, quacked during the song’s coda”.

We only know of one live performance of the song. It was included in the pivotal concert Games For May on May 12, 1967. Possibly this was the only time. Disc & Music Echo heralded Pink Floyd as “the first pop group to appear at London’s swank new Queen Elizabeth Hall, which opened a couple of months ago beside the Festival Hall on the Thames South Bank”. Peter Jenner explained at the time that they “hoped to present a show of completely new material with tapes and films”. For Bike, Julian Palacios writes that a bicycle was “mounted with contact microphones to pick up the sounds of its rotating gears and ringing bell. Two mechanical toy ducks, mounted atop Plexiglas cabinets stage-front, quacked during the song’s coda”.